Over the past fourteen years, as DNASU has continued to grow and expand,its plasmid collection has grown from 5,000 to more than 400,000 clones. But, one thing has remained the same: "the spirit of sharing."

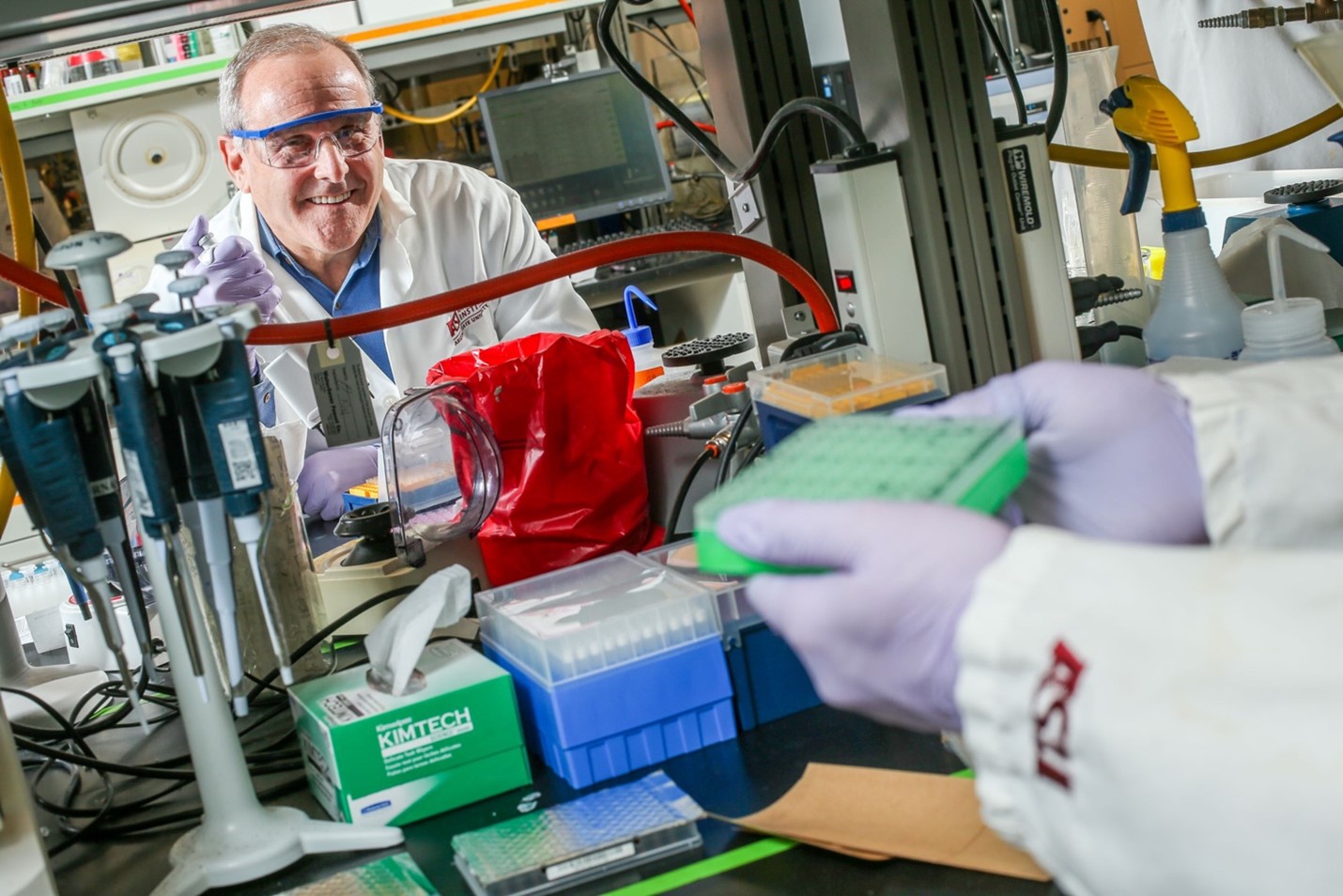

Dr. Joshua LaBaer, DNASU's founder, is proud of this commitment to building the scientific community

"We're here to help all other scientists. We're not hoarding this for ourselves," he said. "The team is really dedicated to quality control and making sure that what they deliver to people is what they promised to deliver."

This spirit of sharing originally began in 2000 when LaBaer launched his first plasmid repository, called Plasmid, at Harvard University. Through a Protein Structure Initiative grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the repository collected, cloned and distributed plasmids to researchers around the world. After LaBaer moved to Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute in 2009, he continued the work with DNASU.

This new beginning gave LaBaer a chance to apply what he'd learned from managing Plasmid. Many changes were made, from improving the automation process of preparing and storing the plasmids, to consistently updating the operating system for the ever-growing database. Most recently, the team is working on moving the plasmids into a new freezer for better storage

DNASU now houses the largest plasmid collection in the world. Despite its size, the repository can tell researchers exactly what each plasmid contains because the team has fully sequenced every clone, a rare feat for similar repositories. Moreover, as a non-profit, DNASU is able to provide less expensive pricing to researchers

LaBaer hopes this convenient resource will help ease the start of future research projects by his colleagues in the scientific community. "You can, these days, go out and order [plasmids] and have [them] made, but it'll cost you hundreds of dollars each time you do that. And if you want to test thousands, that becomes a very expensive thing," he said. "At DNASU, we've got nearly all of them. It's an incredibly comprehensive collection."

LaBaer has been using plasmids in his own research at the Biodesign Institute's Lab of Personalized Diagnostics. The lab produces proteins called biomarkers that help doctors diagnose diseases faster. For instance, the lab is working on a new diagnostic test for Valley Fever, an illness common in the Southwest United States that is caused by local fungi transmitted in the air. Valley Fever is difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are similar to symptoms of a bacterial infection. Using plasmids, the team is able to create numerous copies of fungi genes, which they can test to find the exact proteins that code for and identify Valley Fever. The team has already been successful in finding biomarkers for breast cancer and juvenile arthritis.

As vehicles for gene transport and manipulation, plasmids continue to play an important role in molecular biology. And as more labs are growing their capabilities to house large collections of plasmids, LaBaer hopes DNASU can continue to be a reliable partner in scientific advancement around the globe.

"That's what DNASU is," he said. "It's our opportunity to share all this with the rest of the world."

Back to top